Teaching on-site with the collections is a priority for the Beinecke Library. Direct encounters with materials fulfill a mission of encouraging students to engage with the past, in the present, for the future. In a typical recent year, more than 500 class sessions have been held during the academic year with Yale faculty and students.

In 2020, of course, very little is typical. The public health measures required to confront a pandemic have restricted on-site opportunities. Remote instruction is the default mode. Along with colleagues throughout Yale Library, Beinecke Library staff have swerved to develop new policies and procedures to partner with faculty to ensure academic continuity.

Early on, for example, library curators and other staff rose to the occasion of supporting online instruction by working with instructors to use digitized content in classes on Zoom. Begun in March, that work has continued in the Fall 2020 semester.

Beinecke Library access services and digital services staff have also been adding content extensively to the digitized collections, both to support teaching at Yale and to serve broader academic and public audiences. The library has added more than 175,000 new images to the digital library since quarantine began in the spring, including ongoing efforts to convert PDF images done for individual researchers into TIFF filesto upload to the publicly accessible collections. Since July 1, when a limited number of staff were able to return to work on-site, the Beinecke Library has digitized new content requested by faculty for more than 30 Yale classes.

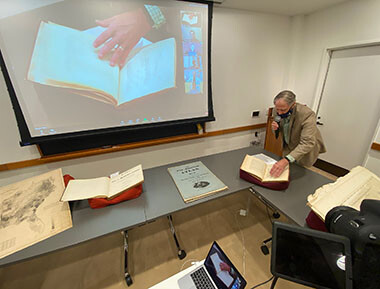

New this fall, Beinecke Library staff are now producing live or pre-recorded sessions from the classrooms featuring curators and/or faculty working with materials as a further means to enhance online instruction for students. Tubyez Cropper, communications associate at the library, leads the filming, while Ingrid Lennon-Pressy, Anna Franz, and their colleagues in access services, coordinate scheduling and materials with instructors from a variety of Yale schools and academic departments.

The library’s longest serving curator, George Miles, was the first back in the classroom to pioneer a new form of virtual instruction. He led the inaugural session on September 14 for Cartography, Territory, and Identity (HSHM 422/HIST 467J), a course taught by Bill Rankin, associate professor of the history of science, that explores how maps shape assumptions about territory, land, sovereignty, and identity.

Miles, the William Robertson Coe Curator of Western Americana, is no stranger to online learning. He developed, with William S. Reese, the Yale Library’s first-ever online exhibition, The Illustrating Traveler: Adventure Illustration in North America and the Caribbean 1760-1895, in September 1996, that remains available now.

Twenty-four years later, Miles was in the classroom with Cropper, both masked and observing physical distancing, sharing highlights from the map collection with Rankin and his students watching and engaging live on Zoom.

Miles explained why this effort is so essential for his fellow curators and educators:

A key aspect of building a special collection is the recognition that for most of human existence words, images, and ideas have been conveyed by physical objects – cave walls, clay tablets, papyrus rolls, animal hides, paper, pieces of tin or aluminum, and even today, screens of one sort or another. One of the reasons that faculty bring students to the Beinecke Library rather than have them just read modern scholarly editions is their appreciation that the very characteristics of the objects – their size, their texture, their design - provides insight into how words and pictures were produced, circulated and used.

Observing those qualities and analyzing them regularly and up close reveals details of technology, society and culture beyond the words or pictures inscribed on those objects. To put it another way, it’s important to see the many ways in which the works of Shakespeare or Dickens or Melville reached an audience or to appreciate the different physical characteristics of the many photographic processes of the 19th century.

Digital surrogates are extraordinarily valuable for making content available to a larger audience than can enter the Beinecke Library, and for students and scholars principally interested in the lexical or graphic content of an item, they can be nearly perfect substitutes for the original. But digital surrogates almost inevitably prioritize the “contents” of a book, manuscript, print, photograph or archive. Even when we include images of a book’s cover or binding, or add a ruler to an image, the nature of digital technology – at least in its current state – struggles to convey the complex characteristics of disparate objects. Very large and very small objects usually end up looking the “same” when we display them on our digital screens. Most digital surrogates are of frozen captures rather than of an object in use. A large map or plate that is carefully folded into a book is seen fully opened, obscuring the physical activity that a reader would have to undertake to open a volume, turn its pages, and unfold an insert to look at it.

So at the same time that high-resolution images in the Beinecke digital library represent an essential contribution to making our collections more accessible, they cannot fully convey seeing multiple originals set next to each other or to handle/use an object as it might have been handled/used at the time of its creation, or by someone a century later. That’s the key reason that most faculty bring students into the physical library rather than just use our wonderful digital surrogates. And it’s the reason why, even though we cannot host classes in the building, we have decided to offer an admittedly awkward hybrid digital approach that attempts to convey to faculty and students some sense of the experience that they might have enjoyed in another time.

By seeing a curator or other staff member display and handle objects in real time we are trying to help students appreciate their size and relative scale; by turning pages we are trying to give a sense of how challenging (or how easy) it was to use a volume; by displaying the closed bound volume and then opening its folded plates we are trying to convey both the ingenuity of a binder but also suggest the kind of use for which a book or volume was intended. And at the same time, we are trying to provide insight into the words or images that are inscribed on the object.

After the inaugural session, Rankin affirmed the value that Miles described. The professor told the curator, “I thought the session went very well – WAY better than just flipping through scanned images in a slideshow. Seeing the actual objects in actual space is so important.”

While essential, Miles recognizes that such remote instruction has its limits and does not deliver the full impact that actual, on-site instruction provides for students and teachers: “My first session impressed on me that it’s virtually impossible to provide the kind of experience remotely for as many objects as you can with students present in the classroom. On-site, multiple students can identify and interact with objects individually. Online, they all have to funnel their experience through the single staff member.”

He also notes, “While there are advantages to streaming live video, it’s a great challenge to control lighting, focus, and resolution in such a way as to convey physical details that could be observed easily in person.” In addition, there are limits to the capacity of staff and library infrastructure as to the volume of classes that can be taught in this way. Where there were often five or more classrooms sessions a day in a typical academic year in the past, at present there is capacity for no more than one per day.

In addition to Miles’s work with Rankin’s class, other sessions scheduled to date in September 2020 have included: Significance of American Slavery (AFAM/AMST 060/HIST 016), a first-year seminar taught by Edward Rugemer, associate professor of African American studies and history; Poetry, Film, Music and Art: John Ashbery’s Work (AMST 390/ENGL 280/HUMS 319), a study of Ashbery through examining the films, music, and art that provoked his imagination and structured and inhabited his poems, taught by Karin Roffman, senior lecturer in the program in humanities and associate director of public humanities; and Six Pretty Good Selves (HUMS/LITR 027), an intensive introduction to studying the humanities for first-year students taught by Ayesha Ramachandran, associate professor of comparative literature, and Marta Figlerowicz, associate professor of comparative literature and of English.

For now, remote teaching is a valuable service and an important additional proxy the library can offer amidst very challenging circumstances. Beinecke Library staff are using the early weeks of experience to improve and enhance what they can do with academic colleagues on campus while online learning remains the predominate mode of instruction. In the future, when on-site instruction resumes, such virtual instruction will likely continue to serve as a way to enhance and extend engagement with the collections.

Ramachandran offered online, via Twitter, an early evaluation of the new online offerings: “Thanks @BeineckeLibrary for amazing support with taking collections teaching online and making it more accessible! Our students had a wonderful time, and thanks to the wonderful Tubyez for terrific camera work.”

* * * *

For those interested in an online proxy of the materials selected for the Beinecke Library’s inaugural virtual session, here are a few items from the list of collection materials from the map collections selected by Miles for Rankin’s course:

Beinecke MS 560: Portolan atlas. Agnese, Battista, active 16th century.

Landberg MSS 556: Masālik al-mamālik, [19th century].

1973 265 Bishop-ricke of Dvrram and Cvmberland, Westmoreland…